When the extension of the Henry Hudson Trail makes its way through Matawan and Aberdeen, it's going to bring with it bicyclists, walkers, runners – and maybe their money.

As the towns push to redevelop the area around the NJ Transit station, the county is pushing to convert an old, inactive rail line into a paved trail that will run for 12 miles from Freehold through the towns. The county plans to hook up the trail extension to the existing Henry Hudson rail trail in Aberdeen. It would run a total of 22 miles from Freehold to the Atlantic Highlands.

If it follows national trends, that trail may boost the area's redevelopment efforts. Across the country, cities are using inactive or abandoned railroad rights of way for pleasure trails as they breathe life into dying business districts or depressed downtowns.

It's part rail romance, part economics. Just as towns sprang up around railroads, businesses have sprung up around the trails that once ran through vacant urban corridors, said Craig Della Penna, the New England field representative with the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy, a non-profit group that has been pushing for such trails for 13 years.

“The same thing happens today with the trail,” Della Penna said. “People and businesses gravitate toward it in ways that you can't imagine.”

Although the municipalities here have little to do with the development of the trail, a county project, they recognize the advantage of having one headed their way.

In Aberdeen, where the town has designated the area surrounding the train station a redevelopment area, and in Matawan, where town officials are pushing for the same move, the trail could bring people downtown.

“That's our expectation, or at least hope, that people will discover Aberdeen and they'll spend their money in the township,” said Aberdeen Mayor David Sobel.

James J. Truncer, director of the Monmouth County Park System, said the county is about to sign a lease with NJ Transit to use an inactive stretch of railroad right-of-way, which runs from Freehold through Marlboro to the existing Henry Hudson Trail, for the project.

The county is also examining the 12 bridges and trestles along the stretch to see what, if any, rehabilitation work they will need for the project, he said.

More than $800,000 has been set aside for the project. The county parks system has set budgeted $400,000 for clearing brush and removing rails and ties, and it has received $426,000 in federal money through the state to help rebuild the bridges. It will take an estimated $550,000 more to build the trail, which will probably be done in phases, said Faith Hahn, a supervising planner with the parks system.

It will probably be about two years before the first part of the trail can be open to the public, she said.

Once the agreement is signed, the county will most likely lease the property from NJ Transit for a nominal sum, and the county park system will build and maintain the trail, Truncer said.

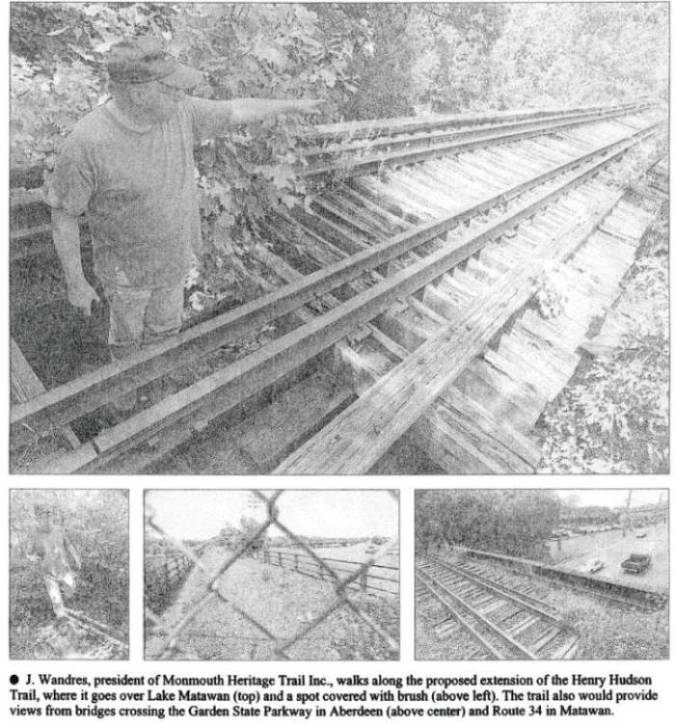

The trains on the old line began running in the late 1800s, and hauled produce to the pier in Keyport, where it would be shipped to New York City and other areas. The last passenger train ran along the tracks in 1954, and the last freight train ran in 1973, said J. Wandres, president of Monmouth Heritage Trail Inc.

On a 60-foot-tall trestle over Lake Matawan, the rails have rusted and some of the ties are crumbling, but Wandres said the structure is still sound, providing a spectacular view of the marsh and wildlife below.

To trail enthusiasts, such as Wandres, scenes like that demonstrate why the old line is a perfect opportunity for the project. Wandres’ nonprofit group, which has about 30 active members, has been pushing for the trail extension since it formed in 1995.

Studies in other parts of the country show rail users spend anywhere from a couple of dollars to up to $50 a day along the way. Because the county is footing the bill for the Henry Hudson Trail extension, that's basically free business for Matawan and Aberdeen, Wandres said.

“That's revenue that doesn't cost anything,” he said. “Towns like Matawan stand to luck out.”

The rail trail may help ease some of the area's parking problems, if commuters chose to bike to the station, which serves about 3,000 people a day, Wandres said.

“That's certainly not going to eliminate the parking problem, but it will reduce it a bit,” he said.

The project is in the county's hands, but towns can support it by putting signs directing users downtown and holding events along the trail, Wandres said.

Meanwhile, Matawan and Aberdeen seem receptive to the idea as they try to breathe life into their shared train station area.

In Aberdeen, the planning board recently approved a luxury 290-apartment complex near the station, and the developer has agreed to pay for a 200-foot section of the trail along the apartments.

Sobel, Aberdeen's mayor, said he enjoys the existing Henry Hudson trail, which runs from the Atlantic Highlands to the Keyport, Hazlet, Aberdeen border. He sees a potential for getting commuters out of their cars and onto bikes.

In Matawan, the trail could bring in people to eat and shop as the town tries to lure businesses, said Ralph S. Treadway, the borough's downtown redevelopment coordinator.

“You're talking more people friendly, a small-town experience where people can see each other and aren't encased in a ton of steel and glass,” he said.

No Regrets

The rails-to-trails movement

began in the 1970s. As rail lines were replaced by highways as the

preferred means of getting grain from field to elevator, railroad companies

began abandoning large chunks of lines, especially in the Midwest.

Activists soon began to try to preserve those rights-of-way.

Today, there are more than 10,000 miles of rail trails across the country, with more than 18,000 miles in the works. New Jersey has 24 trails for a total of 154 miles, according to the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy, with another 15 trails totaling 170 miles in the planning stages.

“No community has ever, ever regretted putting a rail-trail project in,” Della Penna said.

For example, redevelopment efforts in Dunedin, Fla., included a rail trail that runs through downtown.

“The downtown was pretty much dead,” said Jeff Dow, a Dunedin town planner. Instead of people coming downtown for shopping and entertainment, they began going to malls. In the late 1980s, the city, with a population of about 34,000, formed a community redevelopment district. The construction of the Pinellas Trail, which runs from St. Petersburg to Tarpon Springs through Dunedin, began about the same time.

“Those two happened within one or two years of one another,” Dow said. “So it's kind of hard to say which had the more effect…but I think both of them were rather fortuitous circumstances.”

And no one can dispute people use the trail, which is owned by the state and maintained by Pinellas County. The last time the town counted the trail users was 1992, one year after the trail opened. More than 500 skaters, bikers and walkers used it on weekdays, and close to 800 people used it on weekend days, Dow said. He believes numbers have grown since then.

“It goes right through the middle of downtown,” Dow said. “It has brought a lot of bicyclists and walkers and joggers. I think they have patronized a lot of the numerous restaurants and shops downtown.”

And Wandres sees the same future for area businesses along the planned Henry Hudson Trail extension.

“They will come – trust me,” he said. “They will come.”